What can we do this year to help solve climate change while supporting struggling communities that have faced joblessness, sickness and loss? This was what the Master of Environment and Natural Resources Management (MENRM) program of the Faculty of Management and Development Studies (FMDS), UP Open University (UPOU) tackled through a webinar entitled “Climate Solutions: The Philippine Context” on 7 April 2021, 9:00 AM (PHT), via the UPOU Networks.

The event was organized as part of the Solve Climate by 2030, a global dialogue initiative by the Center of Environmental Policy, Bard College, New York. Dr. Eban Goodstein, Director of The Center of Environmental Policy, opened the webinar with an introduction on what the global project is about. This was followed by the welcome remarks given by Dr. Jeanette Yasol-Naval, Padayon Director of the UP System.

To hear local perspectives about steps that could help the Philippines solve climate change, four panelists were invited to share how their different fields of expertise and background could contribute in finding solutions to the climate crisis.

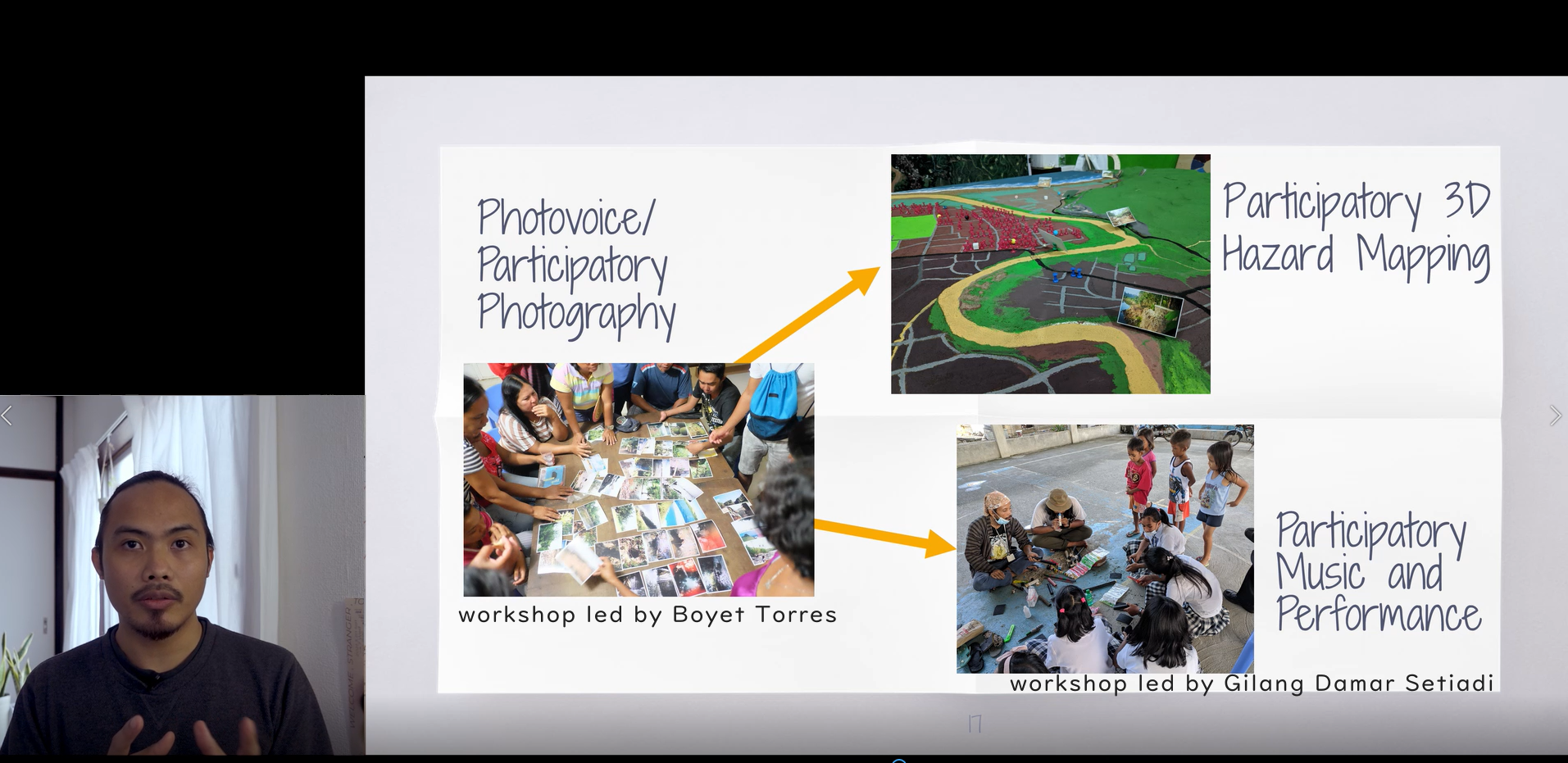

Mr. Ralph Daniel Lumbres, an interdisciplinary visual artist, designer, educator, and woodworker led a discussion on how artists could help with the climate crisis.

“Art is a powerful way to change the mindset of people, to convince, to communicate, and lead to behavior change,” argued Mr. Lumbres as he mentioned how the Renaissance art, the novels of Dr. Jose Rizal, and the documentary film “An Inconvenient Truth” all provided both facts and emotional connection in urging people to do something.

Mr. Lumbres shared his experiences in different art projects and programs that advocate for the environment. One of these is the HANDs! Project that incorporated arts in Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) and environmental education; and as an action plan, led to the creation of the Ligtas PAD, a community-based 3D hazard mapping project. He also founded the Prodjx Artist Community, an interdisciplinary collective art project focused on the environment. Other projects and programs he participated in were the Art for Resilience Communities (ARC) and Collaboratoire 2020 organized by UPOU.

“Being an artist is being expanded. There are new ways, now more than ever, how to practice art,” stated Mr. Lumbres as he challenged institutions, organizations, and the academe to “create more space for interdisciplinary collaborations [and] to find more ways for artists and other creatives to participate in projects”

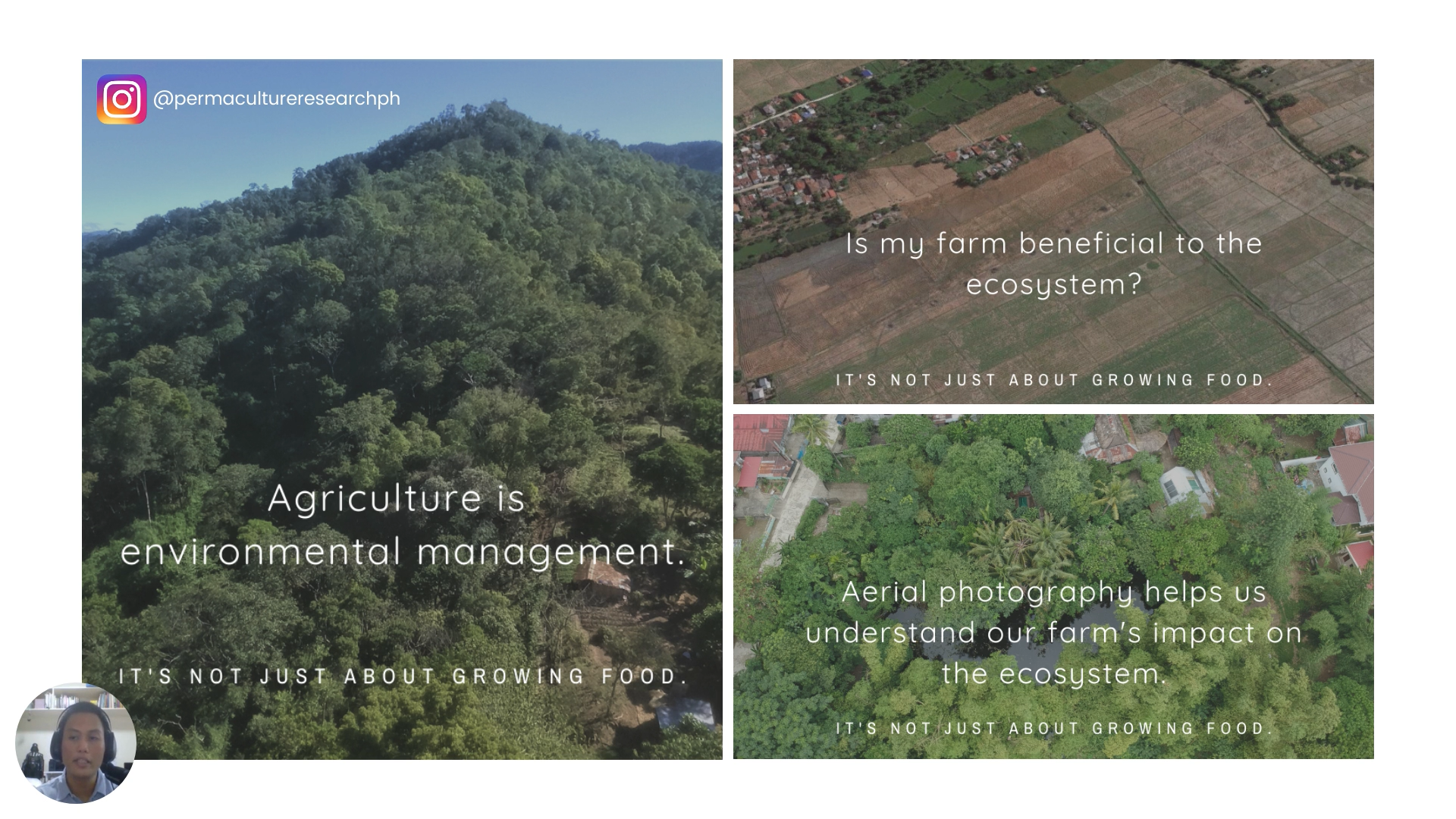

Meanwhile, Mr. Jabez Joshua Flores — a MENRM graduate and PhD graduate of Environmental Science — talked about climate solutions through permaculture, a design philosophy integrating ecology, agriculture, and landscape design.

“What often gets overlooked is the negative impact of agriculture in our ecosystem and climate. Sadly, agriculture is an extractive culture. In order for us to have a space to grow our food supply, we have to compete with other plant and animal species. But with the permaculture lens, we can actually view agriculture as environmental management,” explained Mr. Flores.

With this, he suggested to start by getting to know the landscapes first. Simple designs at home could include rainwater catchment systems and planting more trees to provide habitat for birds.

“Start simple and start small, but start now. The complexity of your design will grow as you gain experience and wisdom,” concluded Mr. Flores.

In the third presentation, Mr. Marlon Martin, Chief of Operations at Save the Ifugao Rice Terraces Movement, discussed the utility of indigenous knowledge as a climate solution. He focused on agriculture and food security, land use and environmental sustainability, and community values or customary laws.

In discussing the indigenous concept of land stewardship, Mr. Martin quoted a Kalinga elder, “Such arrogance to say you own the land when in fact the land owns you, or how can you own that which outlives you?”

He remarked that while this saying may be said in a different context, the meaning holds true in the climate change discourse, “Land is life, so is water and air. We’re all just passing through, but with the responsibility of passing it down to the next generation, preferably in a better state than when it was passed down to us.”

The Indigenous Peoples’ (IP) intricate knowledge system of rice terracing was described as a “fine example of indigenous knowledge in agriculture”. Through this practice, IPs were able to sustain their community production even with limited and hostile mountain conditions but not at the cost of their natural environment.

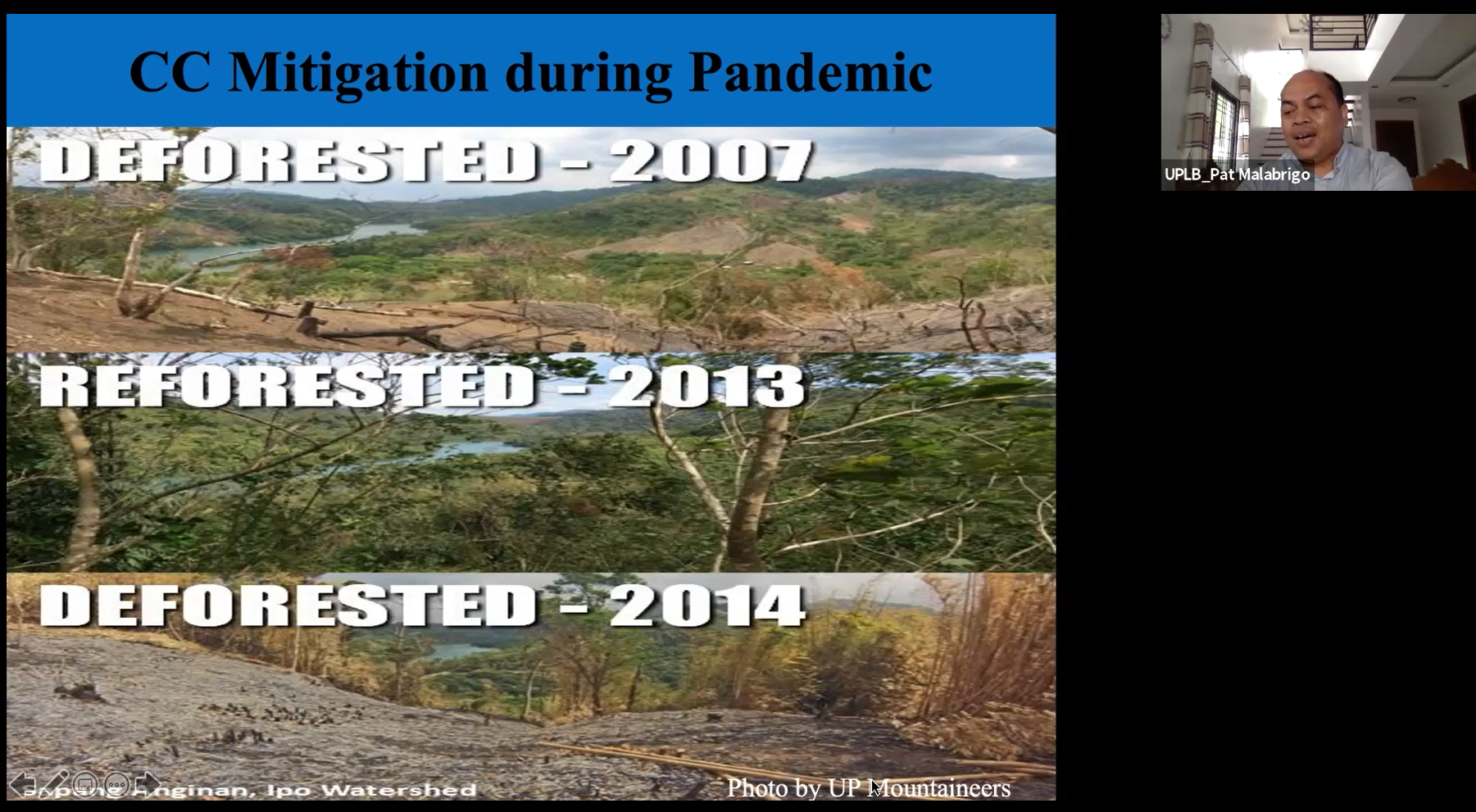

Lastly, Prof. and For. Pastor Malabrigo, Jr., Associate Professor of Plant Taxonomy and Forest Biodiversity in UP Los Baños (UPLB), talked about carbon, forest, and climate.

Prof. Malabrigo focused on forest management as key to successful climate change mitigation — even when compared to reforestation and to reduction in deforestation. As cited in The Philippines 2nd national communication to the the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 2014, he shared that “Philippine forests are significant sinks of carbon” attributed to 100 millions tons of carbon.

At the national level of forest management, Prof. Malabrigo shared that the government allocates billions of pesos to the National Greening Program (NGP), described as the greatest hope of Philippine forest. “But,” remarked Prof. Malabrigo, “Isn’t it ironic that while we are spending a lot of money to bring back the gone forest, we are at the same time allowing illegal poachers, charcoal makers, and kaingineros to take down our existing forest resources?”

Aside from environmental restoration, the NGP also aims for poverty eradication. With this, Prof. Malabrigo encouraged the practice of community-based reforestation which could provide alternative livelihood to upland communities. Another option was to encourage and facilitate small forest-based industries.

With the increase of people’s interest in plants during the pandemic, Prof. Malabrigo hoped to use this time to introduce native plant species with great ornamental value while at the same time providing livelihood to legitimate growers.

An open forum was also conducted after the four presentations. Participants sent their questions via the UPOU Networks chat box, YouTube comment box, and Facebook comment section. Dr. Consuelo dL. Habito, MENRM Professor and Program Chair, served as the moderator of the webinar.

Dr. Primo Garcia, Dean of FMDS, closed the webinar by challenging students and teachers to #MakeClimateAClass.

Dr. Joane V. Serrano, Associate Professor at FMDS, UPOU spearheaded the event, together with Dr. Habito. More than 100 universities in different countries and states have also joined the week-long dialogue from April 6 to 14.

Participants of the webinar were encouraged to make their own pledges to help solve climate problems through these links: pledge by teachers and students, and pledge by the general public.

The webinar can be rewatched through the UPOU Networks.